To interpret and preserve the artistic heritage of Washington, D.C., the ‘Uptown Interview’ transcribes candid conversations with the artists, curators, personalities and amplifiers of the District’s creative ecosystem.

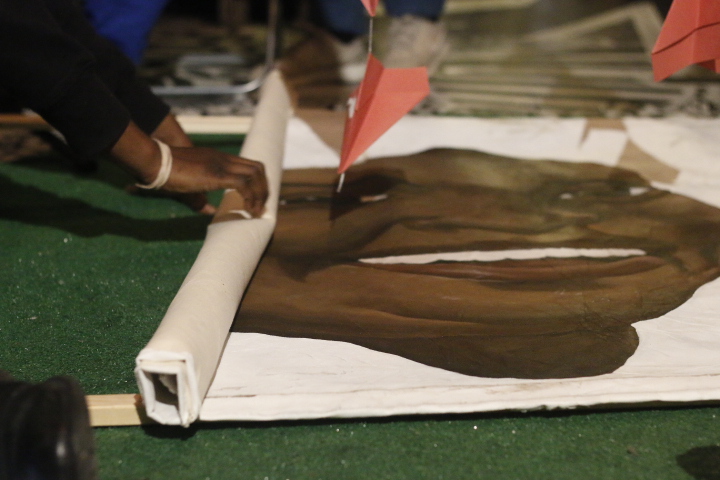

Wifigawd released his latest album Stuck in 95 executive produced by Dretti Franks on Wednesday. Polaroid by Maxwell Young

At 23 years old, Wifigawd has amassed streams and credits that would alert any listener in tune with the rappers and internet culture fueling the current generation of hip-hop. He’s shared the stage with Smokepurpp, $uicideboy$, CHXPO, and Thouxanbandfauni, while pulling in features from others like an InTheRough favorite, Warhol.SS. No Jumper, the YouTube channel becoming less underground everyday, also debuted Wifigawd’s video to “Sippin’ on Drank” several weeks ago. The internet enables this kind of reach, and thus the opportunity to travel and grow a fan-base on an inter-state level. As far as home-base is concerned, though—the District of Columbia—Wifigawd’s music wasn’t always in the frame of mind. “Niggas out here weren’t even fucking with me,” he said of his hometown. He still resides in Northwest, D.C.

Times have changed, however, and a recent show at Songbyrd Music Cafe in Adams Morgan with ascending Houston rapper Maxo Kream is a prime indicator. “I tore the roof off that bitch,” he said acknowledging the home field advantage. “This is my fuckin’ city!”

Regardless of the eyes watching and ears listening to the image and sound of the Uptown Souljah, the context that has informed Wifigawd’s music is rooted in his Northwest, Washington heritage and collaborations with other like-minded DMV artists.

It started at home. The emcee’s parents instilled a deep fervor for hip-hop growing up. “They wanted me to know who A Tribe Called Quest was before I knew who Lil’ Wayne was…who KRS-One was, De La Soul, all the greats, Big Daddy Kane, Rakim—real hip-hop,” he told me over pizza and football, the latter I found out he no longer supports.

Citing a household vinyl collection of over 2,000 records, there was no need to listen to radio, even though his folks forbade it. Instead, they took him to see legendary wordsmiths live and direct at the notorious 9:30 Club. “I’ve been going to shows since I was five years old,” he said. “I just know they were letting a little-ass nigga in the club with his parents.”

Perhaps it is these experiences and influences that explain Wifigawd’s pre-millennium/early 2000s aesthetic he reinforces with his FUBU-dripped music videos, ‘FUBU 05’ project (which he regards as a third of his “Holy Trinity”), and ‘Stuck in 95’ album he released this past Wednesday. “I know everything that’s going on, but I’m still stuck in the past. I’m stuck in a time warp in my mind,” he said.

Aside from the music, an artist can choose to share or not share whatever storyline he/she/they want. They can be as open as Wiz Khalifa’s DayToday vlogs or as cryptic and secretive as Beyoncé and H.E.R. Certainly though, knowing more and having a greater understanding of the backgrounds and creative processes of your favorite artists can change the perspective of your listening.

I first saw Wifigawd last June at Uptown Art House. The whole place went berserk that evening and I experienced a classic DIY rage that left me dripping in sweat from head to toe. At that point, Wifigawd filled the placeholder for turnt rapper. Then, I took to Apple Music to find his six full-length projects dropped in 2018 alone. This hardened, turned-up persona also flexed melodic cadences and catchy hooks. And now after talking to him, I know how big of a role writing is to the execution of his verses. We have to be mindful that the self-made, anyone-can-do-it mentality of the internet can also obscure the real time and mastery people put into their craft.

“I do it all. That’s just the swag…That’s the most important thing: you’ve got to have the swag,” he said.

Listen to ‘Stuck in 95’ by Wifigawd at the end of the transcript.

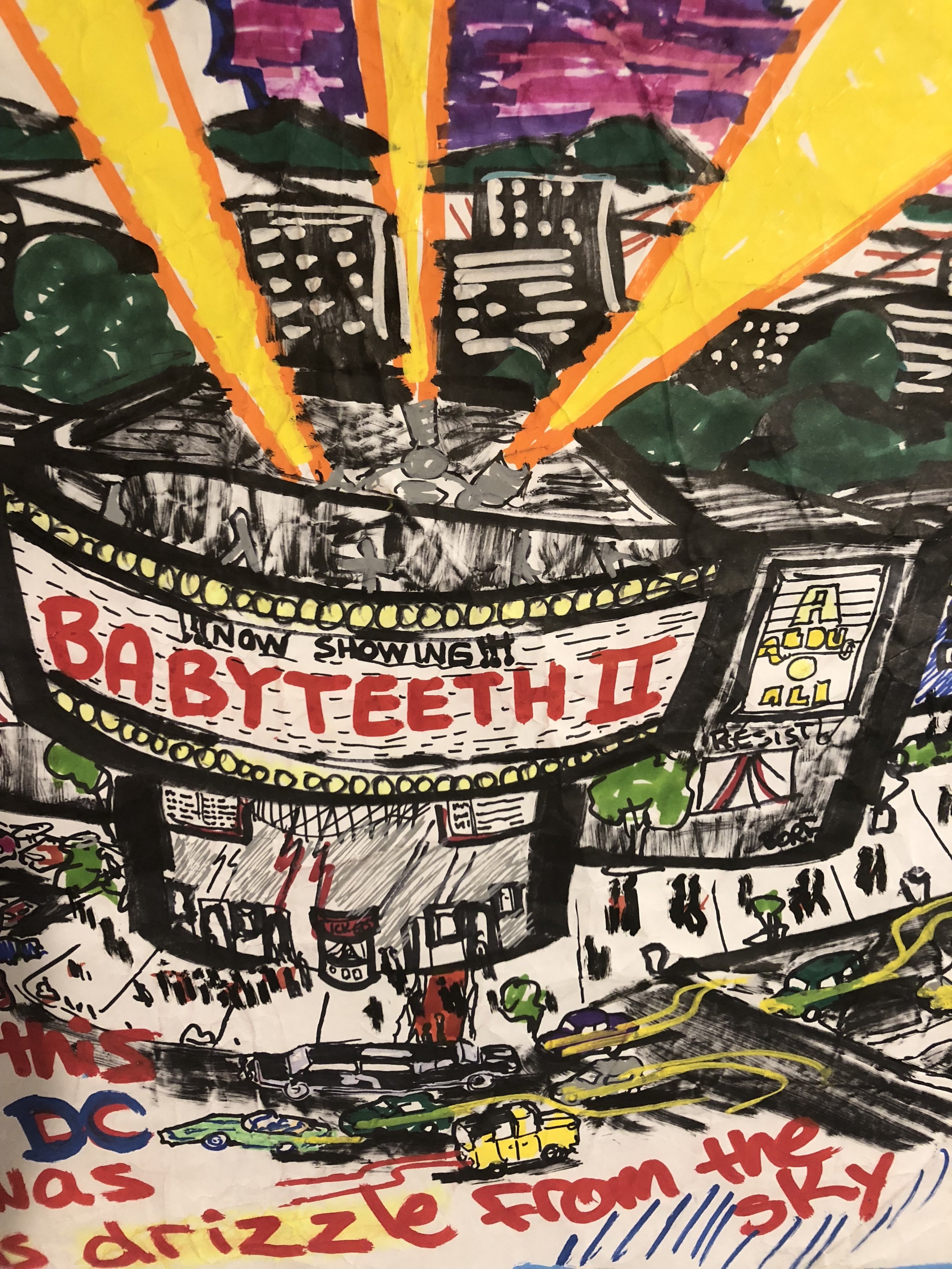

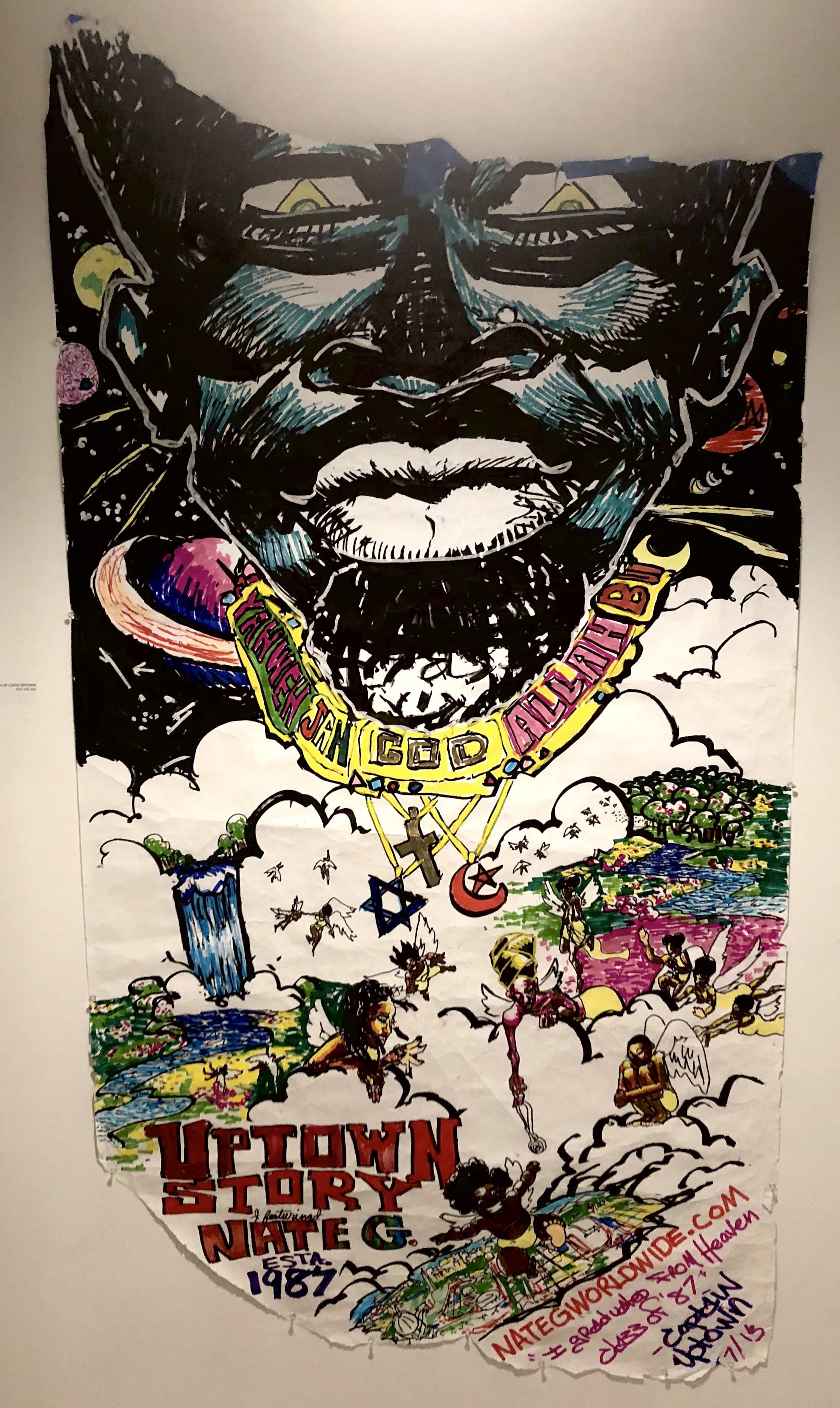

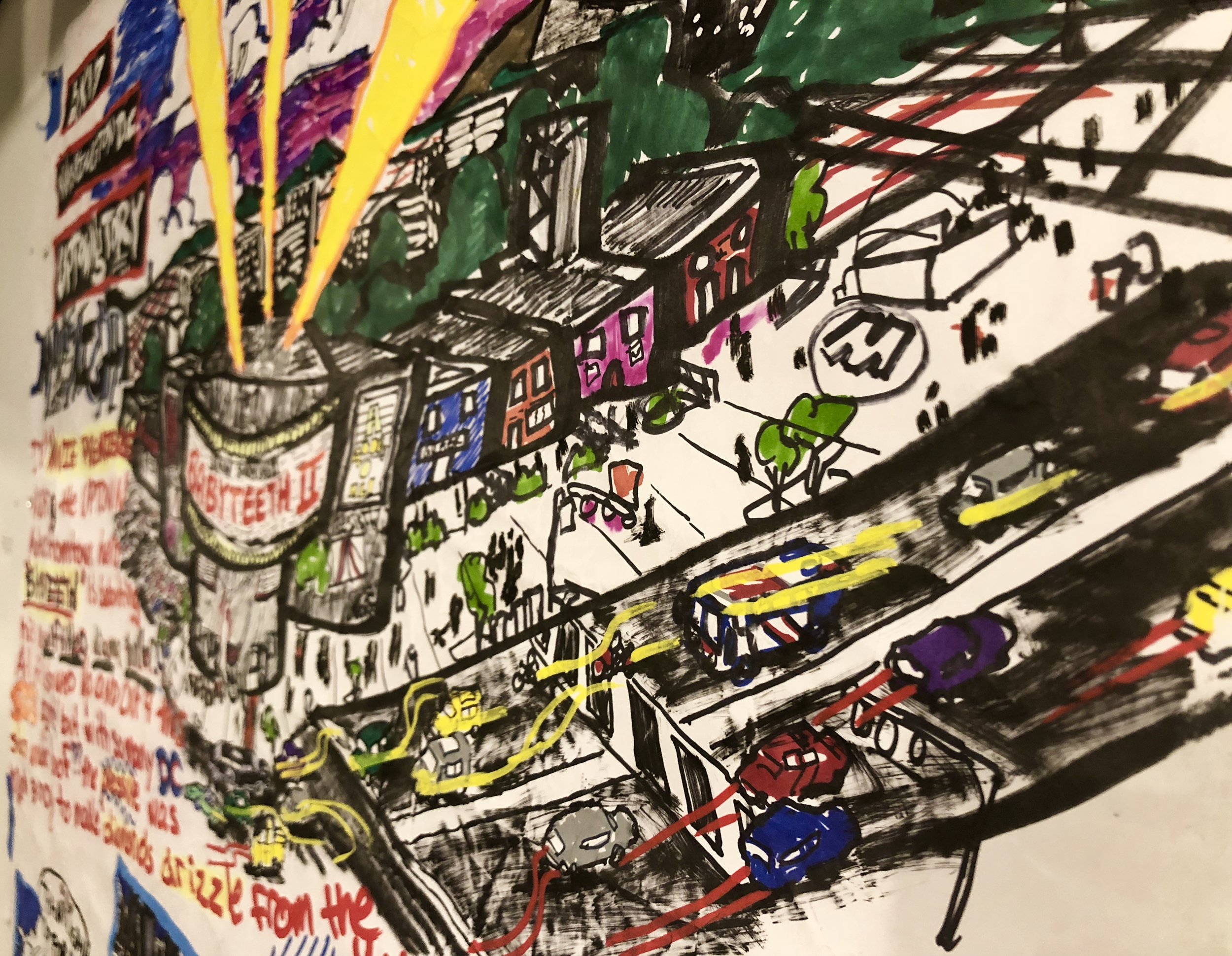

[Plays “Full Quart” by Nate G]

Maxwell Young: Do you keep up with D.C. music?

Wifigawd: Not many people. Who is this?

MY: Nate G.

Wifigawd: I fuck with Nate G.

MY: When you started to realize what the D.C. music community was, who was responsible for introducing you to it?

Wifigawd: MartyHeemCherry was one of the main niggas who got me hip. I’ve known bro forever, since high school...I just check out my friends new music.

MY: Who is that?

Wifigawd: The Khan, Chachi--the gang. Everyone I’m with, and if not, I’m looking for new Black Kray shit. Anytime niggas play some new crank around me, or some random artist, I fuck with the joints. I just don’t go looking for it unless I hear one of my friends play it.

[Plays “Duck Sauce”]

Wifigawd: What the fuck is this?

MY: This is NeckMusic.

Wifigawd: NeckMusic, oh, Ceez?

MY: Yeah. Iodine, Downtown Dawson, and Ceez.

Wifigawd: I fuck with Ceez’s beats. I don’t know who this is rapping.

MY: Where does the name “Uptown Souljah” come from?

[Laughs]

Wifigawd: It’s complicated. It’s a breed of Uptown niggas--fly niggas. Being from Uptown, niggas are fly. They get to the bag...They have good weed...It ain’t like that no more. So, if few niggas are out there like that, they are some soldiers. Real Uptown shit--U.P.T Souljah.

MY: What’s the “Souljah” aspect to your name?

Wifigawd: I used to fight everybody. I used to be a Bama.

MY: Talk about some early fights.

Wifigawd: Shit, that’s why I got kicked out of my school, for fighting. I don’t like talking about fighting because I used to fight a nigga for no reason. I guess not for no reason, but out of disrespect or some shit. That shit goes all the way back to fourth grade. I remember I was at lunch and I had on a white polo, fresh as shit, and this nigga threw some mashed potatoes on me. I hit his ass across the table. His ass was just sitting right there, huffing. I just cool it now, I’m not with the fighting shit anymore. I’ll still throw some hands, though.

MY: Take me through some of these legendary shows, the ones you can remember.

Wifigawd: I remember 2016--New Year’s. It was me, Black Kray, and Lil’ Tracy in Richmond, Va. That’s Kray’s hometown, you know, so that shit was lit. I remember another joint in Richmond at the same spot with me, CHXPO, and Kray. That was 2016. Another legendary show I did was this joint with Smokepurpp, Thouxanbandfauni, CHXPO, and me. I could probably find the flyer, it was called Kings of the Underground in LA. That shit had endless people in it. I had another show in LA. It was with DJ Smokey, Lofty, Slug Christ, and The Khan. That was pretty sick. Then I did this joint in New York with Dash, Madeintyo, Ugly God, Sporting Life, and we opened the joint. We made that show lit. The show with Maxo was pretty hard. My first show out of town was when I was 18. I had that jont in Dallas, Texas--$uicideboy$.

MY: Are you out in LA a lot?

Wifigawd: Not really. I go out there if I have a show.

MY: How did the No Jumper connect happen?

Wifigawd: [Adam22] has been following me on Twitter. I just hit him up and told him I had a video for him, he said bet.

MY: That video goes. The song goes more importantly (“Sippin on Drank”), but the visual is nice. I just got hip to Moshpit DMV. I always see him around, what’s his name?

Wifigawd: JJ.

MY: Yeah, I’ve seen him everywhere. Do you collaborate a lot on music videos?

Wifigawd: Yeah, that’s my boy.

MY: Can you take us to a low point in your rap career? A specific time where you felt discouraged.

Wifigawd: When I first started was the lowest point because niggas don’t fuck with you. They don’t send you any beats or anything like that. That’s the lowest point: dealing with bitchass producers.

MY: Where was your first show?

Wifigawd: I don’t know, bro, I’m trying to think about it.

MY: Or a moment where you felt like, ‘Okay, I can move forward from here.’

Wifigawd: Niggas weren’t even fucking with me out here, bro. This is 2014. They were not fucking with me. I was like whatever, ‘Fuck you stupid-ass niggas.’ I had a friend who went to VCU and I said, ‘Boom. This is what we’re about to do. Listen, I see you setting up these little house parties. I have rap songs. I’m going to come rap.’ I probably still have the footage of that shit--turnt the fuck up. Those were my first shows. Niggas were turning up at my shit, so I was like, ‘Oh, yeah, this the wave out here.’ We did three or four of them jonts. I had a little group back in the day called Portal Boyz.

MY: Like how you were describing your music as “void.”

Wifigawd: Yeah, like some void shit.

MY: You said D.C. wasn’t fucking with you. Has that influenced where you play in the city?

[Laughs]

Wifigawd: I’ve always been the type of nigga to do me. I know niggas be dick-riding because I see that shit from the outside. Y’all niggas just dick-ride whatever is hot. I’m not mad, that’s what you do. That’s definitely by default because everybody else is doing it. So when it’s time for everybody to do what I’m doing, I won’t be fucking with everybody.

MY: You say that Stuck in 95 is unlike anything made in the last 15 years. What does it mean to you as far as where you are in your development?

Wifigawd: It’s showing everybody that I can do rap. Sometimes I hate whenever you try to classify me. I can rap.

MY: You’ve been talking about weed a lot, as far as needing to be high.

Wifigawd: Yeah, I fuck with weed.

MY: Why is that? Where does it put you?

Wifigawd: I’m hyper as shit. If I don’t smoke I’ll start tweaking and get sporadic as if I was high on some other shit. But when I smoke weed, I just feel normal. I smoke in my music videos, yeah. I fuck with weed. I’d rather promote weed than violence...on some Curren$y shit. He’s a good example of how to be a G-ass nigga with good content. Niggas know he’s not a bitch. Niggas know he’s about that shit, but his content is on some fly shit.

MY: Who are some of your favorite Instagram follows?

Wifigawd: I like following all the OG rappers just to see what the fuck they’re doing.

MY: Which OG rapper is a good follow besides Snoop Dogg?

Wifigawd: Tommy Wright III. Follow that man. His shit is turnt. He still does shows.

[Laughs]

[Plays “Diamonds” by Rob Stokes]

Wifigawd: Who’s this, King Krule?

MY: Rob Stokes.

Wifigawd: Oh, I fuck with Rob. I was in the studio with him one day. I jih like passed-out, but I heard it the whole time. It was him and Trip Dixon collaborating on jazz shit. It was fire. He’s tight.